We asked Melinda Baldwin, who specializes in the history of scientific journals, to offer some thoughts on Randy Schekman's recent editorial in the Guardian. Melinda is currently finishing a book, Making Nature: The History of a Scientific Journal, to be published by the University of Chicago Press. You can learn more about her work here.

On Tuesday, Nobel Prize-winning biologist Randy Schekman

made a startling announcement: he intends to boycott three top scientific

journals—Science, Nature, and Cell—that published much of his Nobel-winning research. According to Schekman, these “luxury journals” are “damaging” and

“distorting” science. As researchers, funding

bodies, and tenure committees have focused on brand

names and impact factors, the quality of papers—and of science—has declined.

|

| Top Journals Science, Nature, and Cell (Image Source) |

Schekman’s editorial naturally sparked my interest—I am

currently finishing a book about the history of Nature—and made me think about journal prestige in the twenty-first

century. The three “luxury journals” certainly don’t lament their status as the

world’s most sought-after scientific publications. In Nature’s case, this level of prestige is (as I argue in my book)

partly the result of a conscious effort by several Nature editors to attract interesting papers and make Nature a desirable place to publish new

research.* But it is also bottom-up: for decades, researchers have chosen to publish in Nature, and it is this role of contributors I want to explore today.

As more and more contributors chose Nature, the increase in submissions drove down the acceptance rate—which only made publication there more desirable. Thus, researchers and publishers get caught in feedback loop. Certain

journals are considered prestigious largely because they accept so few

submissions, and in turn they receive a large number of submissions because they are

considered so prestigious.

Schekman suggests two ways to break this cycle. First, the

luxury journals could stop “artificially restricting” the number of papers they

accept and raise their acceptance rates. Second, and more provocatively,

Schekman points out that contributors could stop sending papers to luxury journals—and announces that his lab will no longer submit papers to Science, Cell, or Nature. Schekman says he’s taking this step to try and “break the tyranny

of the luxury journals” and he encourages other researchers to join him.

Could contributor pressure really change how a scientific

journal operates? As a historian, I'm allergic to making

predictions about the future, so instead I will say this: it has in the past.

Nature was founded

in 1869 under the leadership of the astronomer and British War Office

bureaucrat J. Norman Lockyer, with the backing of the London publishing house

Macmillan and Company. Lockyer had a very specific vision for his new weekly

journal: he wanted Nature to be a

publication written by men of science** but accessible to laymen.

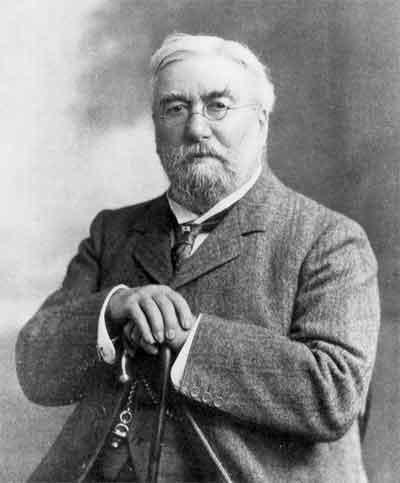

|

| Norman Lockyer (Wikimedia Commons) |

In his initial circular asking for contributions, Lockyer

was careful to emphasize that Nature was

not a specialized scientific

journal. Instead, Lockyer hoped that Nature

would become weekly reading for Britain’s most influential barristers,

businessmen, and members of Parliament. His ultimate goal was for Nature to help convince prominent

Britons that science was an important endeavor that deserved intellectual

respect (and also significantly more funding).

British men of science, however, proved less interested than

Lockyer had hoped in writing journalistic articles aimed at an audience of

laymen. Instead, Lockyer found himself with a pile of specialized, technical

submissions that would have been near-incomprehensible to anyone without a

scientific background. His contributors simply did not send him the

journalistic pieces he wanted, and Lockyer was not about to turn to science

journalists (of whom he had an extremely low opinion) to fill the gap.

Determined that Nature’s

articles should be written

exclusively by qualified researchers, Lockyer printed his contributors’ technical

submissions. By 1872, the clergyman Charles Kingsley—a man with wide-ranging

knowledge of recent scientific research—found himself compelled to tell his

friend Lockyer that Nature was no

longer accessible to laymen. “I have the highest respect for [Nature], and I wish I were wise enough

to understand more of it,” he wrote in a letter to Lockyer. “But I fear its

circulation must be more limited than you would wish.”

|

| Original Masthead of Nature (Wikimedia Commons) |

When an article in Science

or Cell or Nature can make a scientist’s career, as it can today, it can be

easy to see the editorial staff as the all-powerful gatekeepers of scientific

success. But Schekman’s editorial and the early history of Nature remind us that readers and contributors are not passive

nodes in the network of science publishing. Whether one researcher’s boycott

will have an impact remains to be seen, but we should not discount the power of

contributors to shape the development of a scientific journal.

______________________

* Although I feel compelled to mention that Nature’s current editor, Philip

Campbell, has been a consistent critic of the over-use of impact factors and

other measures of “prestige” or “importance.”

2 comments

Color design of your blog is very nice. About Randy Schekman this time with not much happening palgiat include sources that they use as a reference. ask permission to share miraculous science journal htpp: //www.journalcourse.com

Aspirants who want to pursue their career in journalism can appear for courses in mass communication. In Australia, there are a large number of mass

communication colleges, which offer different Courses in English journalism, radio and television journalism and advertising

and public relations.

research journals

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.