Unless you’ve been living under a rock for the past few

months, you’ve probably heard of Serial,

the podcast sensation taking the internet by storm. Hosted by Sarah Koenig, the

podcast is a serialized account of the 1999 murder of Hae Min Lee, a 17 year-old

senior at Baltimore’s Woodlawn High School. In the style of a true crime drama,

Serial revolves around the

fundamental question: whodunit. But

in this case, there is also a possibility of wrongful conviction. Koenig’s entry

into the story comes through the family of Adnan Syed, Lee’s ex-boyfriend, who

was convicted of 1st degree murder in her death. Koenig set out on a

year-long investigation of the case, pouring over trial records, interrogation

transcripts, even the prosecutor’s evidence files. Was Syed wrongfully

convicted? If he didn’t do it, than who did?

Serial, a spinoff

of the popular NPR podcast This American

Life, has attracted an incredible amount of media attention. Time, New York Times, and The Atlantic have all covered the podcast. Slate began its own

meta-podcast to discuss Serial each

week. Some of this coverage has focused on allegations that racial prejudice pervades

Koenig’s reporting. Because the case focuses on the murder of a Korean-American

teenager by her Pakistani-American boyfriend, Koenig (as a white journalist) is

reporting on communities in which she is a cultural outsider. Others have

criticized Koenig for making herself, as narrator and amateur detective, the

protagonist of someone else’s story.

I discovered Serial

after a few episodes had already aired. I have listened to all of the available

episodes thus far, and for the most part have enjoyed listening to the show. Today,

the highly anticipated final episode of Serial

will go live. Before I listen to the final episode, I wanted to share a #histstm perspective on the show and its surprising success.

Reasonable Doubt?

At its core, Serial is

a reflection of the nature of truth. The show is fueled by uncertainty, as

Koenig brings the listener through a series of “buts,” “what-ifs,” and “wtfs” that

will make your head spin. Adnan was primarily convicted based on the testimony

of Jay, his friend and alleged accomplice in disposing Hae’s body. Jay’s

testimony is riddled with inconsistencies. It doesn’t help that Jay provided

his testimony on four separate occasions: two pre-trial interrogations and two

times on the stand. Koenig meticulously pokes at these inconsistencies, in

hopes that by picking apart Jay’s testimony, the case against Adnan will

unravel.

What struck me about this was how little the testimony’s

inconsistencies bothered me. It seemed intuitive to me that if you told a story

four times, under great pressure and in extraordinary circumstances, that it

would change a little each time. Yet, it is these inconsistencies that drive

Koenig’s uncertainty, as well as the entire Serial

narrative. Her discomfort seems to grow out of the fact that testimony used

to convict someone of first-degree murder shouldn’t be full of holes, and

potentially, full of lies. Such uncertainty appears to be an assault on our

standard of justice, and in particular the belief that we must prove guilt

beyond reasonable doubt.

The question then becomes: how much doubt is “reasonable” in the context of the criminal justice system? There are piles of scholarly work on this topic, but as layperson it was not something I had given much thought. In Episode 8, “The Deal With Jay,” Koenig interviews Jim Trainum, a private investigator, former homicide detective, and expert on false confessions. I think that their conversation really gets at the heart of the issue. Trainum, while admitting that the inconsistencies were troubling, also acknowledges that investigators were “better than average” in handling the evidence. He explains that the detectives in the case didn’t push on Jay’s inconsistencies, the way that Koenig is, out of fear of creating “bad evidence.” Jay was the prosecution’s star witness: the entire case hinged on his testimony. If the investigators pushed too hard, there would be nothing left for them to use, and their case would fall apart.

Koenig balks at Trainum’s use of the expression “bad

evidence.” “All facts are friendly!” she exclaims, “You can’t pick and choose.”

Trainum responds by explaining that for prosecutors, the goal was not to get at

absolute truth, but to build a strong case. Koenig doesn’t back down: “How can

you build a good case, how can he be a good witness, if there is stuff that is

not true or unexplained?” Trainum concludes by suggesting that in any case,

there will always be things that are unexplainable. He also points to the

possibility of confirmation bias: the prosecutors were looking for facts to

support the theory they already believed to be true.

In a weird way, Trainum’s explanation brought me back to

Kuhn’s explanation of normal science: that as evidence accumulates, the

underlying assumptions of a scientific theory go unquestioned. It is only when enough anomalies accumulate

that scientists will begin to question the tenets of their current paradigm.

For Koenig, any anomaly or inconsistency should be enough to throw the

conviction out the window. But as Trainum points out, there are important

consistencies that check out, and give credence to the theory that Syed is guilty.

In the absence of alternative explanation, it becomes a compelling case.

Another unsettling feature of the case is the absence of

physical evidence. In Episode 7, Koenig interviews lawyers in the “Innocence

Project” at University of Virginia School of Law. The students reviewing the

case are unanimously unconvinced of Syed’s guilt. One student claims that there

are “mountains of reasonable doubt.”

The sticking point for these students is the absence of

physical evidence. Although a liquor body found near Hae’s body was scraped for

epithelial cells, they were never tested. Fibers found in the soil around her

body were only tested against a very small number of fabric samples. There were

no DNA tests performed on the body itself. Some of the forensic reports from

the case appear to be missing from the records.

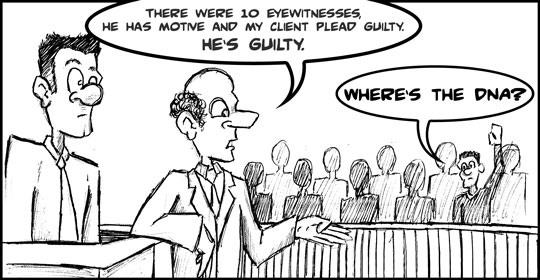

Could these students be suffering from the “The CSI Effect?”

This expression is used to describe an increasing demand among jurors and the

wider public for forensic evidence, which is attributed to the popularity of

television crime shows like CSI. Studies have shown that frequent viewers of

CSI may place a lower value on circumstantial evidence, and many lawyers argue

that there has been a significant shift in the behavior of juries. Could Koenig

(as well as the listener’s) uncertainty be a side effect of 15 years of

television that glorifies forensic science? Is one person’s testimony enough to

put someone away for 1st degree murder?

Interestingly, there was actually a cutting-edge technology

that was introduced into the trial: the cell phone. Syed’s case was one of the

first in Baltimore Country to use cell phone records and tower pings as

evidence in a criminal trial. Syed himself had only purchased a cell phone

three days before the crime occurred, a fact that was used to throw suspicion

onto him. The ways in which the cell phone records and cell phone tower pings

confirmed Jay’s testimony lent significant strength to the prosecution’s case.

Reddit and the Radio

Lastly, I want to reflect on why Serial’s surprising popularity. After all, as a genre serialization

is nothing new. Literary serials date back to the 17th century, and

surged in popularity during the Victorian era with Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers. More recently,

serialized stories were the bread and butter of television networks everywhere.

Daytime soaps, prime-time dramas, even some reality shows are versions of the

serial form. And not that long ago, before Netflix allowed us to mainline

entire seasons of the Gilmore Girls

in a weekend (no judgment), viewers had to wait with bated breath for the next

installment. Maybe Serial’s charm

derives from being an old-school radio show in an era of immediacy and

on-demand entertainment.

Another interesting phenomena to pop up in Serial’s wake is the creation of a subreddit

dedicated to the show. As of the time of writing, the subreddit has almost

30,000 followers. Posters propose alternative theories, map cell phone pings,

and share detailed timelines of the crime. Important figures in the case,

including Adnan’s brother and Jay, are rumored to be posting in the group. The

group’s activity reminds me a little of citizen science, where the collection

or analysis of large amounts of data is crowd-sourced by non-professionals. Perhaps

this collision of an old-school serial and the universe of social media can

help explain the show’s popularity. The pleasure of waiting for the next

installment is further intensified by discussion and speculation within an

online community.

For weeks, listeners have expressed anxiety about the ending

of the show (it even inspired a Funny or Die parody). After all, Koenig is investigating a real case, not reciting a

script. And in real life, we don’t always succeed in finding the truth. Koenig

has acknowledged this pressure, but insists she has no special responsibility

to provide listeners with a satisfying conclusion. We will soon find out!

2 comments

Thanks for this subtle and engaging post on Serial. I listened to all of the episodes as they appeared and was as gripped by it as most. Discussing it with my spouse, who is a former federal prosecutor, has been enlightening. While I applaud your post overall, I think you make a couple of claims, both involving Koenig's motivations or beliefs, that are either false or unsupported by the content of the episodes. In particular, I think there aren't grounds for asserting B and C below.

"[A] Koenig meticulously pokes at these inconsistencies, [B] in hopes that by picking apart Jay’s testimony, the case against Adnan will unravel ... [C] For Koenig, any anomaly or inconsistency should be enough to throw the conviction out the window."

Though I agree there were times when Koenig seemed to clearly believe in Adnan's innocence, I don't think, per B, that her reporting was motivated by that belief. I also don't think that Koenig was ever so uncareful as to believe, per C, ANY anomaly or inconsistency was grounds for a not-guilty charge.

Hi Matt,

Thanks for reading and for your comment!

Upon re-reading, I think you are right that both statements B and C are somewhat unfair to Koenig. In my experience as a listener, I had become quite frustrated with what seemed at times to be Koenig's dogged belief in Adnan's innocence (an opinion that I don't necessary share). My comments are colored by that frustration. In her defense, however, she was always very open about narrating her own experience of the investigation, including her vacillating ideas about Adnan's innocence and guilt - a big part of what made the show so gripping. While Koenig did investigate the case at Adnan's sister's behest, exoneration wasn't the sole motivation of her investigation. Instead, I think she made her best effort at discovering the "truth" - as elusive as that turned out to be!

The have since listened to the final episode which I think crystallized a few things for me. Koenig's final conclusion (spoiler alert!) that she would ultimately acquit Adnan did confirm some of my previous suspicions that quite apart from Adnan's innocence or guilt, Koenig had decided the jury did not have the evidence to convict him. I will concede, however, that this wasn't just based on "any anomaly or inconsistency." Koenig's rationale for acquittal was certainly more complex than that. I'm still not sure where I stand in the whole matter, which I think is a credit to Koenig's excellent reporting.

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.